Edward’s return voyage to England was slow, hampered no doubt by the lingering effect of his wounds. He also had unfinished business to attend to before he set foot in his new kingdom. For it was now his kingdom. Shortly after landing at Trapani in Sicily, he was informed of the death of his father, Henry III, who had passed away on November 16th. Edward had previously learned of the deaths of his eldest son, John, aged just five, and his uncle Richard of Cornwall. This was a bitter treble blow, but Edward did not, as might be expected, hurry home to secure the vacant crown.

His first objective was to avenge the murder of his cousin, Henry of Almain, butchered at Viterbo the previous year by the sons of Simon Montfort. To this end Edward travelled to Rome and hence to the city of Orvieto, where the new Pope, Gregory X, was in residence. Here he was welcomed with great ceremony by the assembled cardinals and taken to see the Holy Father. Edward had the advantage of knowing Gregory personally, since the latter had previously visited England. In the course of their discussion, he persuaded the pope to order Guy Montfort to appear in person before the papal curia. Guy failed to comply, so Gregory laid sentence of excommunication upon him. This had no effect either, and Edward’s efforts to raise a military force to hunt down the murderers were unsuccessful.

After he had left Italy, Guy appeared before the pope in a penitent’s garb, begging for absolution. By the early 1280s, he and his brother had been restored to the favour of the papacy. Edward’s frustrated desire for vengeance may have been eased by the knowledge that his cousin’s killers would remain forever notorious for their crime. When Dante Alighieri wrote his Divine Comedy early in the next century, he condemned Guy Montfort to the seventh circle of Hell, neck-deep in a river of boiling blood.

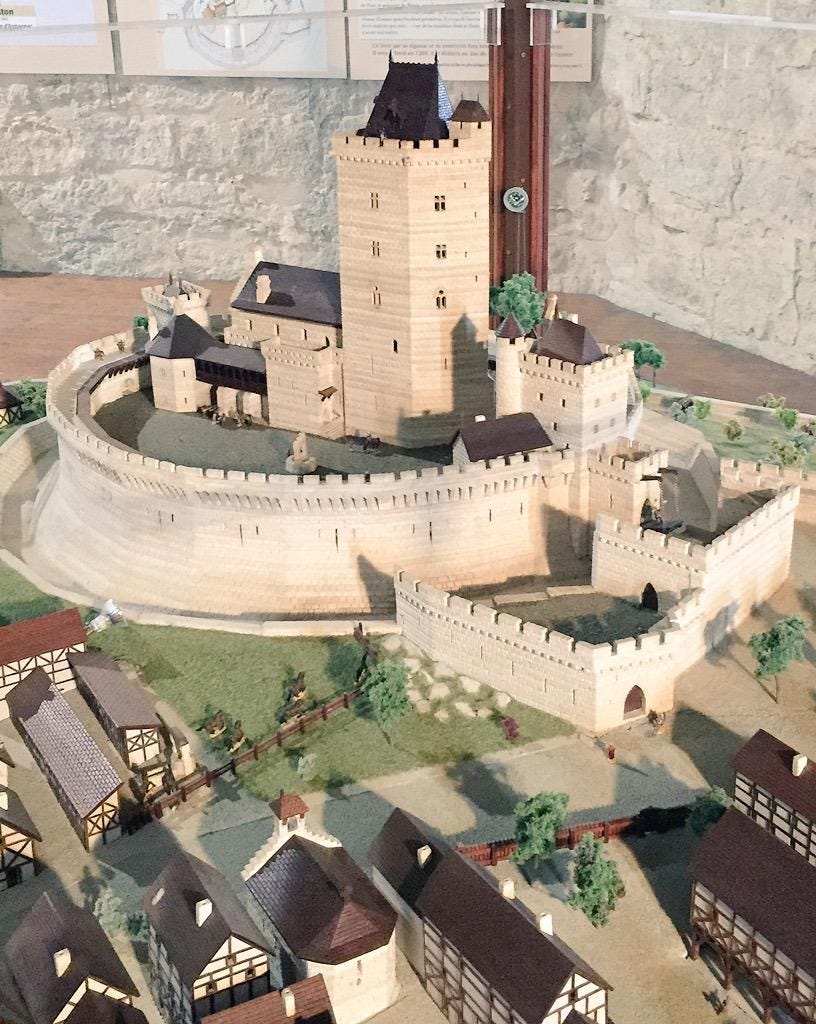

From Orvieto Edward travelled through the north of Italy, being entertained in grand style along the way. After traversing the Alpine pass at Mont-Cenis he entered Savoy in south-east France, where he stayed at the castle of St Georges d’Espéranche, close to Lyon. This was a new castle, not yet complete, and its architecture may have influenced the design of Edward’s future castles projects in Wales:

‘...the castle of St Georges d’Espéranche itself, with a symmetrically planned inner ward and octagonal towers, has some obvious general resemblance to the Edwardian castles. St Georges has one very precise link with Harlech [in mid-Wales], for the form and measurement of a latrine chute, at the abutment of curtain wall and corner tower, are just the same in both castles.’

In more general terms, Edward’s visit to Savoy would have considerable influence on his Welsh campaigns. Elements of typically Savoyard design can be found elsewhere in his castles, and he would employ many Savoyard masons and constables in Wales. This subject will be examined in more detail in Book II.

During his time at St Georges, Edward also took the opportunity to settle another score. William de Tournon, the robber knight who had plundered Edward’s troops on the way to the Holy Land, was summoned by the Count of Savoy to atone for his conduct; this appears to have been done under threat of force, since William did not technically owe fealty to anyone. On 25th June 1273, in the presence of the count, William was forced to pay homage for his lands to Edward. Thus, from being a baron who held his estates in freehold and could act with impunity, he became a vassal of the King of England.

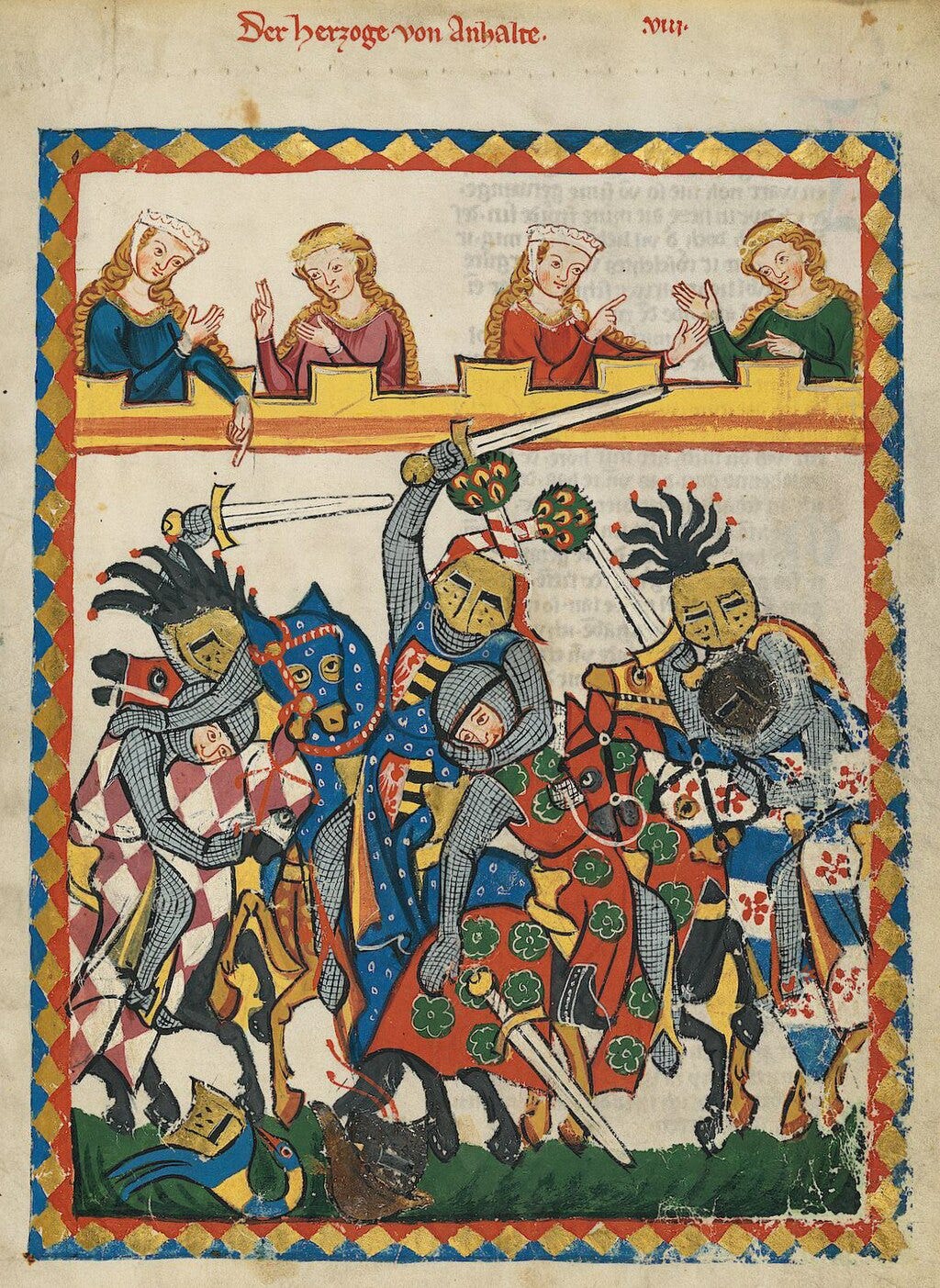

From Savoy Edward travelled north towards Paris. On the way he was invited to take part in a tournament at Chalon-sur-Saône in eastern France. The invitation was a trap, and the tournament degenerated into a real battle from which Edward was lucky to emerge in one piece (I will describe the Little Battle of Chalon, as it was called, in a future post).

He reached Paris safely and there did homage for his duchy of Gascony to the new French king, Philip III. Thanks to the Treaty of Paris in 1249, Edward was obliged to acknowledge Philip as his overlord in Gascony. This put Edward in a compromised position, whereby his own Gascon subjects could appeal over his head to the King of France. It was a weakness Philip and his heirs were keen to exploit.

War in Gascony

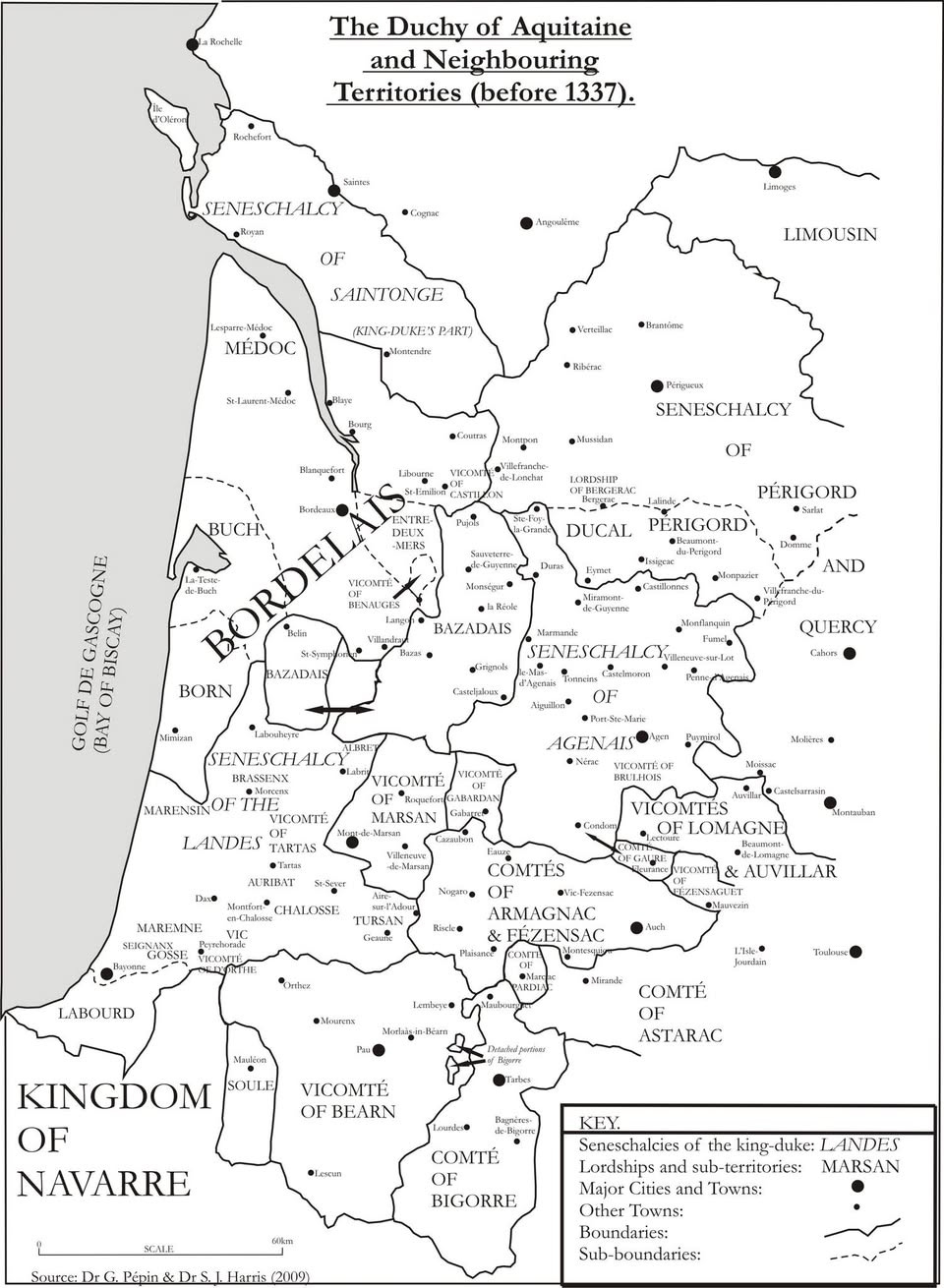

In early August Edward left Paris and went south to take the homage of his Gascon vassals. He marched with great pomp to Bordeaux, ‘by voice of herald and by sound of trumpet’, and hence to St Sever in southwest Gascony, where he received the homage of the Gascon nobles. Or most of them. Gaston Béarn, one of the most powerful and troublesome lords of Gascony, was conspicuous by his absence. In September the king-duke sent a knight, Gérard Laur, to summon Gaston to perform homage. In response Gaston’s men seized the envoy, maltreated him and threw him into prison.

Edward had not campaigned in Gascony since his teens. The duchy had been quiet in the intervening years, and efforts were made to secure Gaston’s loyalty. In 1270 he was supposed to accompany Edward on crusade, though the deal fell through. The marriage of his daughter, Constance, to Henry of Almain in the same year was part of the same attempt at conciliation. This met with disaster when Henry was murdered in Viterbo. Thereafter Gaston’s touchy pride appears to have been ruffled by the new Seneschal of Gascony, Luke Tany. Like Simon Montfort before him, Tany governed the duchy with a firm hand. His firmness – or harshness, depending on one’s perspective – roused the ire of the local lords.

Edward, conscious of his delicate status as a vassal of King Philip, did not immediately punish the ill-treatment of his envoy. Instead he went to St Quitterie, near Auch in the south of Gascony, and there summoned Gaston to meet him. Gaston did not come, but sent a message saying he was willing to answer in court for any allegations made against him. At this point Edward lost patience, had Gaston arrested, and threw him into prison in the castle of Sault. This lay in the extreme south-west of the duchy, in the foothills of the Pyrenees (now the region known as Pyrenees-Atlantiques).

Gaston was only allowed to recover his liberty after promising to submit to the judgement of the court at St Sever, and to hand over to Edward the castle and town of Orthez, in particular those men who had maltreated Gérard Laur. This oath was sworn in the presence of two bishops. Suspicious of Gaston’s good faith, Edward made him re-swear the oath with three Gascon knights as guarantors. One of these men was Arnald de Gaveston, father of the famous Piers who became Edward II’s favourite and (alleged) lover. If Gaston broke his oath and left the royal court without permission, it was declared he would lose all his lands. No privilege or custom could protect him, and he would be excommunicated into the bargain.

Edward’s suspicions were well-founded. Gaston did not consider himself bound by his oaths, and managed to slip custody. The account of his escape is remarkably similar to that of Edward’s at Hereford in 1265:

‘So he [Gaston], riding one day with his keepers for the sake of exercise, mounted a destrier horse, which he had cunningly procured, and fled away, finding a multitude of his armed followers at no great distance.’

Gaston and his followers made their way back to Orthez, where he doubled the garrison. Again Edward hesitated before resorting to arms. Instead he summoned a court at St Sever. Here it was decided that if Gaston rejected one more summons, the king-duke was justified in raising an army against him. Edward’s actions demonstrate his awkward position as a vassal of the King of France. He could not act against rebels like Gaston with impunity and was careful to observe local procedure and custom before resorting to military action.

Predictably, Gaston failed to obey the summons. At the start of November Edward gathered his forces and marched into Béarn. Histories of Edward’s reign tend to skate over this campaign, remarking merely that Gaston was swiftly brought to heel. Contemporary sources paint a different picture. Wykes describes a gruelling, thankless campaign fought at great expense and in dreadful winter conditions, much like Edward’s later wars in Wales. Gaston’s lordships of Béarn and Bigorre lay in the southern part of the duchy, bordering the Pyrenees, where he had a string of castles. Methods of warfare in Gascony had changed little since Montfort’s day. The Gascons rode out by night to kill and rob, carrying off stolen goods to stock their well-fortified strongholds. They inflicted much damage on the countryside as well as Edward’s troops, who also suffered from cold and lack of forage, since the rebels had stripped the countryside. Thomas Wykes describes the campaign:

‘Moreover, Gaston, having known in advance about the king’s arrival, considering that he was unequal in strength, and fearing that the king’s power, which had been incomparable, was being put to the test with the little company, which he had assembled, he thought that they should go to a certain mountainous province, which was surrounded by hills in such a way that it used to have almost inaccessible entrances and exits. Indeed, in the same province he had erected five impregnable castles…whose attendants, frequently coming and going and attacking the king’s army in sudden assaults, more frequently inflicted not immoderate losses, and returning pompously with the booty they had captured, they were protecting themselves by the defence of the fortifications. Therefore, the king stayed for almost the whole of that year with a copious army in Gascony, overrunning the wildernesses of the same province, and completely accomplishing nothing, but rather using up inestimable money, which he caused to be unsuitably wiped from the kingdom of England. Certainly, there was such a great scarcity of victuals in his army, and an unusual dearth of them, because both men and cattle were wasting away by starvation and hunger. At length, with certain messengers mediating about peace, but nevertheless, as will be clear from what happened afterwards, being busy in deceit with deceptive machination, the parts submitted themselves in turn to the arbitration of the king of the French.’

For Edward, the war must have come as a reality check. Far from his noble endeavours in the Holy Land – fruitless as they were – he was back to fighting fellow Christians, and his own subjects to boot. Nevertheless, he stuck grimly to his task. Gaston was forced to retreat:

‘Edward went to his [Gaston’s] land with a powerful army, and forced him to flee to a castle in a strong and fortified position, and here he was besieged.’

The name of the castle is unfortunately not revealed, but it was most likely Gaston’s stronghold at the Chateau de Moncade, near Orthez, where he had doubled the garrison. Gaston himself does not appear to have been at the castle, since he managed to send an appeal for aid to the King of France. No lord with any sense could afford to be bottled up inside his castle by superior forces. The usual strategy was to remain at large outside and try to organise resistance to break the siege. There are plenty of examples of this: Roger Mohaut, for instance, a Marcher lord in Wales, left his stronghold at Mold to be attacked by the Welsh while he mustered a relief force.

The castle soon fell, though Gaston remained at liberty. At the end of November Edward scored another success when Gaston’s daughter, Constance, surrendered to royal forces at Mont-de-Marsan. The nearby castle of Roquefort (‘fort on the rock’) was also seized by Edward’s troops. At the same time the mayor, jurats and commune of the town swore to support Edward in his war against the rebels. Gaston suffered another loss when his castle of Chateau d’Urgons, north-east of Orthez, was captured. Things now looked bleak for the lord of Béarn. His skirmish tactics had failed, and one by one his fortresses were being steadily reduced by the superior forces of the king-duke. King Philip chose this moment to intervene and ordered the rival parties to lay their dispute before the French parlement in Paris. This must have been frustrating for Edward, who was winning the war and held the balance of power in the duchy. For Gaston, a legal dispute was his only hope of salvation.

Gaston had his day in court. He appeared as plaintiff before Philip and charged Edward with destroying his property in Béarn; this was dishonest, since the people of the region submitted claims of damages against Gaston, not Edward. Perhaps realising this, Gaston went on to publicly accuse the king-duke of treason and false judgement. He demanded a trial by combat. Several of Edward’s knights, including William Valence and Aymard de la Rochechouard, were outraged by the Gascon’s presumption and offered to fight the duel on their master’s behalf. A French knight, Giles Noaillon, wrote a letter to Edward offering to do the same. Gaston refused all these challenges and declared he would only fight the king-duke in person.

For his part, Edward was not about to submit to the embarrassment of fighting a judicial duel against his own vassal. King Philip was also uncomfortable with the notion and ruled that the combat would not go ahead. Instead he brokered a truce – the document of which unfortunately does not survive – whereby both parties came to an agreement. ‘Perfect and solid harmony’ was supposedly restored between Edward and Gaston, and the latter’s castles of Roquefort and Chateau d’Urgons handed back to him. The harmony didn’t last long. In February there was fresh trouble at Bazas, south-east of Bordeaux, where two royal esquires were murdered and Edward’s seneschal Luke Tany locked out of the town.

Edward was out of all patience with Gaston and Gascony. In April he left the entire affair in the hands of his lawyers and departed for England. He was delayed at Limoges, where the citizens begged him to defend them against the territorial ambitions of the local French vicomtesse. Their entreaties moved him to tears, but he was too canny to risk provoking King Philip. Limoges had long between a source of dispute between England and France, and the situation might easily have spiralled into war. Instead he took the fealty of those who wished to give it and moved on, leaving a small English garrison in the city. A month after Edward’s departure William Valence, at the head of a small Gascon force, laid siege to the predatory vicomtesse’s castle at Aixe. This was doubtless done on Edward’s orders. The siege was halted by the arrival of a French envoy, who ordered the contending parties to submit to Philip’s arbitration. As in Gascony, the affair was eventually settled by legal means.

In July Edward finally took ship for England. It was high time the king returned to his kingdom. In Edward’s long absence an old enemy had resurfaced to threaten the ever-fragile stability of England. The man of whom Edward had once been ‘sore afraid’, Robert Ferrers, Earl of Derby, was back in arms.

Very informative, on a subject often treated in a cursory manner if not overlooked entriely.