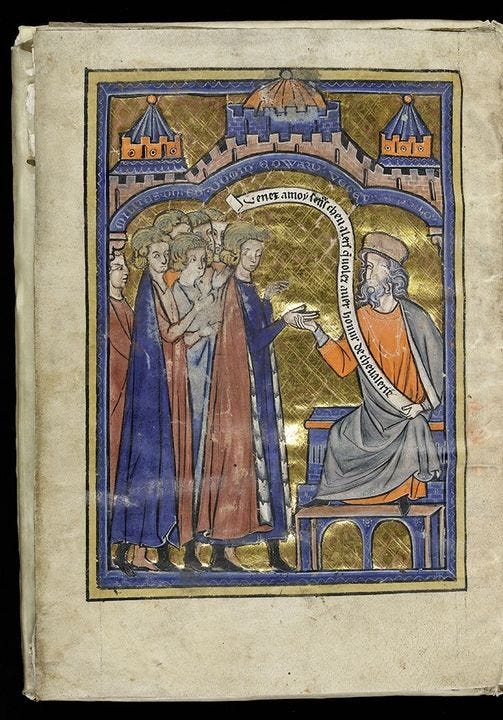

On Sunday, 24th June 1268, Lord Edward and hundreds of knights and barons formally took the Cross at a specially convened parliament at Northampton. Edward’s wife, Eleanor, also swore the vow. Women had formerly been discouraged from accompanying their husbands on crusade, but by this time it was not uncommon for those of high rank to go: Eleanor Montfort had done so in the 1240s, as did Queen Margaret of France. The event was carefully managed, and meant to project an impression of unity and reconciliation after so many years of conflict.

The idea of an English crusade had been mooted since 1253, when Henry III and his then 14-year-old son, Edward, first took the Cross. They did not enrol to fight in the Holy Land, the usual destination for crusaders, but to go to Hungary and help repel an invasion of pagan Mongols. This unlikely idea was soon dropped and replaced with an even unlikelier one: Henry exchanged his crusading vows for a doomed bid to win the crown of Sicily for his younger son, Edmund. His brother Richard of Cornwall was also asked by the pope to engage in the defences of the eastern frontiers of Christendom.

Not until the late 1260s, when the storms of civil war and political crisis had finally blown over, was a crusade seriously reconsidered. The papal legate, Ottobon, raised the subject in Parliament in February 1267, only to meet with a dispiriting response. There was still much resentment against the influence of foreigners in England, and he was suspected of wanting to remove young Englishmen from the land so they could be replaced with aliens. Ottobon refused to be discouraged. He took to preaching to the public through interpreters, as well as employing English friars to carry his message up and down the land. This failed to rouse much popular support, and it seems that much of the impulse for the crusade stemmed from Edward.

Edward had been contemplating the idea for some time. He had previously sought papal advice, and in January 1268 the Pope, Clement IV, sent a letter strongly advising Edward not to go. Edward, however, was committed. There is no reason to think his motives were anything other than genuine piety, concern for the fate of Outremer, and the demands of honour: the sons of the King of France had sworn to go, therefore the sons of the King of England should do the same.

Background

There was urgent need for a new Crusade at this time. The power of the Egyptian Mamluks (‘Mamluk’ originally meant slave), had risen to new heights under their ruthless and capable sultan, Baybars, who had defeated the Mongols in a series of campaigns and now threatened the Crusader states. In 1265 Caesaera and Arsuf had fallen to the sultan’s forces, followed by the castle of Safad in 1266. Two years later the Mamluk swept on to capture Jaffa, followed swiftly by the collapse of the Principality of Antioch.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was in no condition to resist the tidal wave of Mamluk success. Earlier crusades in the thirteenth century had proved dismal failures. The most recent, under King Louis of France – known as Saint Louis for his piety and commitment to the crusade – had collapsed in an abortive effort to attack Damietta at the mouth of the Nile. Embittered by his failure, Louis spent years trying to organise another expedition. His efforts were blocked by internal disputes and power plays among the Christian states. Not until the Papacy had concluded its feud with the Hohenstaufen dynasty of the Holy Roman Empire, and Louis’ brother Charles of Anjou had secured his position in southern Italy, did a new crusade become a possibility.

Preparations

It was one thing to declare an intention to go on crusade. Finding the cash to pay for such a costly expedition was another matter. England’s resources were depleted, and Edward was obliged to scratch about for money. The clergy could not be taxed directly, since Pope Clement had already levied a tax on them in 1266 to pay off King Henry’s debts and expenses. Funds were raised by the church in other ways, such as the sale of indulgences, but these alone were not enough. In 1268 the government decided to impose another tax after all, on both church and laity, though the process was difficult and the final amounts were not collected until the spring of 1270. In the summer of 1269 Edward obtained more funds by visiting the French king, Louis, and negotiated a loan of 70,000 livres tournois (about £17,500). Louis’ famous piety didn’t prevent him imposing severe terms on the loan. Edward was required to promise to be at Aigues-Mortes, on the Mediterranean coast, to embark by 15th August 1270; he also had to hand over one of his sons as hostage to the agreement, and repayments of the loan were to begin in 1274. 25,000 livres from the total amount would go to Gaston Béarn, the rebellious Gascon lord, to support him on the crusade. King Henry, allegedly moved to tears, gave his consent to the agreement. In the event Edward was not obliged to give up one of his sons, and no objections were raised to his failure to arrive at Aigues-Mortes on time. As for Gaston Béarn, he did not in the end accompany the expedition.

Apart from financing the crusade, Edward’s other task was to assemble enough men. The core of the force was made up of members of his own household, knights retained by Edward, fed and clothed and provided with horses at his own expense. They were recruited on a professional basis: in July 1270 formal contracts were made with eighteen men to raise a total of 225 knights. Only two of these contracts survive. One, detailing the agreement between Edward and Adam Gesemue, a knight of Northumberland, is worth quoting:

‘...know that I have agreed with the Lord Edward…to go with him to the Holy Land, accompanied by 5 knights, and to remain in his service for a whole year to commence at the coming voyage in September. And in return he has given me, to cover all expenses, 600 marks in money and transport – that is to say the hire of a ship and water for as many persons and horses as are appropriate for knights.’

Assuming the other contracts were drawn up along similar lines, this reveals that Edward’s knights agreed to serve in the Holy Land for a wage of 100 marks each per year, with Edward agreeing to meet the costs of sea-transport.

The other captains were made up of Edward’s relatives, close friends and associates, all of whom had served him loyally in the recent wars. Prominent among these were his brother Edmund, Henry of Almain, William Valence, Roger Clifford, Roger Leyburn, Hamo Lestrange, and Edward’s close friend Thomas Clare. Others who received letters of protection for going on crusade included the Savoyard Otto Grandison, William Latimer, Robert Tiptoft, Luke Tany and Pain Chaworth. A letter of protection was a form of surety, and protected an individual and his lands from prosecution or legal action while serving overseas. Complete lists survive for those men who received such letters for Edward’s crusade, though these do not confirm the total number that actually went. Some may have found substitutes to go in their place, or commuted their vows for a monetary payment. Those former rebels who received letters for the expedition included John Vescy, John Segrave and John Eyvill, the aggressive northerner who had assisted Gilbert Clare to capture London. Of these, only Vescy is known to have definitely gone to the Holy Land, though the mere fact the others were listed speaks for their reconciliation to the crown.

All these men would go on to form the nucleus of Edward’s royal household when he became king, and serve in his many campaigns. Many had already formed close ties with Edward in the toils of the 1260s. The tough experiences of the crusade must have bound them tighter still to him.

The glaring exception to the above was Gilbert Clare, Earl of Gloucester. Since his submission at London in the summer of 1267 relations between Clare and the royal family, Edward in particular, had again deteriorated to the point of armed conflict. Edward was not guiltless for the collapse in relations. The terms of the Treaty of Montgomery had deprived him of almost all of his once vast estates in Wales, leaving only the lordship of Montgomery and South Wales: the Trilateral Castles of White, Skenfrith, Grosmont, and the crown domains of Monmouth, Carmarthen and Cardigan. His dwindling power in the west was further threatened by Clare’s claim to Edward’s town of Bristol. A private quarrel blew up between the two men, and it was even alleged that Edward was showing too much interest in Clare’s wife, Alice Lusignan. Perhaps this was mere gossip, but Alice was a famous beauty, and in 1267 she and her husband did start to live apart.

Edward’s preparations for the crusade were further disrupted by the barbarous conduct of his one of his closest allies, John Warenne, Earl of Surrey. In 1268, before Edward took the Cross at Northampton, Warenne entered into a petty row with Henry Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, over rights to some pasture land. The row turned violent, and civil war briefly threatened to flare up again when both men raised armies. Fortunately there was no battle, since they feared to come to actual conflict. King Henry sent justices to mediate between the two factions, and the final judgement went in favour of Lacy. The embittered de Warenne promptly entered into another angry dispute with a baron named Alan de la Zouche. This time he decided to settle the matter personally. In the king’s own palace of Westminster, Warenne drew his sword on Alan and his son, and left them both lying in a pool of blood. Fearful he had murdered them, Warenne fled the scene. He holed up in the castle at Reigate, where Edward was obliged to go with an army and flush him out. Warenne begged for mercy, which was granted on condition he made amends for his crime. Fortunately for Warenne, both his victims recovered from their injuries, though he failed to pay in full the compensation owed to them.

With so much violence and mistrust in the air, the fragile peace could have shattered at any moment. Edward’s uncle Richard of Cornwall, that talented diplomat, came to the rescue. He convinced his nephew and Clare to submit to arbitration, and mutual agreement was reached in the summer of 1270. Clare agreed to follow Edward to the Holy Land within six months, and receive the hefty sums of 8,000 marks if he cooperated with Edward in the venture. If not, he would only receive 2,000. Clare was reluctant to hand over certain of his Welsh castles and manors as surety, but on this point Cornwall was unyielding. Finally, after much horse-trading, Clare came to terms. All this politicking proved so much hot air, for Clare never fulfilled his crusading vow. The resumption of Welsh attacks on his estates in South Wales gave him a convenient excuse not to go, nor did he hand over his castles to royal custody. The main practical benefit of Clare’s agreement was the removal of the last obstacle to Edward’s departure.

Journey to the Holy Land

Edward’s voyage to the distant East was fraught with danger. Things went awry from the start. His initial plan was to sail from Portsmouth to his duchy of Gascony, to visit his brother-in-law Alphonso of Castile and then meet Louis at the agreed rendezvous at Aigues-Mortes. However in early August Edward was informed that Boniface, the Archbishop of Canterbury, had died. Edward wished to see his own preferred candidate, Robert Burnell, installed in the vacant see. From Portsmouth he rushed to Canterbury, where he reverted to the crass bullying tactics of his youth. He and his men smashed open the locked doors of the chapter house and tried to intimidate the monks into accepting Burnell. The clerics, probably shocked by Edward’s behaviour, refused to bow to his pressure. Next month, on 9th September, they elected one Adam of Chillenden as archbishop instead.

Edward’s antics at Canterbury did him little credit and achieved nothing except delay. From there he most likely went to Dover and hence to France on 20th August, abandoning his earlier plan to visit Gascony. His journey through France to Aigues-Mortes was not as straightforward as he would have liked. On the way his army passed through Tournon in southern France, a region infested by robber barons. One of these, William Tournon, had a castle on the Rhône River, from where he would ride out to attack his neighbours: his sole occupation, it was said, was ‘plunder and rapine.’ William held his lands as ‘alod’ (freehold), which meant he owed feudal allegiance to no lord, and thus there was none to restrain him. When part of Edward’s army wished to cross the river, William and his men barred their way and insisted on exacting a toll. They also robbed the crusaders of some of their gear and supplies.

Edward had no time to punish the insolent robber knight. He pressed on to the walled seaport at Aigues-Mortes, only to find the main expedition under King Louis had already sailed. Here Edward was informed of a drastic change in plan. Instead of sailing directly to the Holy Land, Louis had been persuaded to go to North Africa instead and launch an attack on Tunis. This was due to the influence of Charles of Anjou, King of Sicily, who convinced Louis that such an attack would weaken Egypt, which depended on food supplies from Tunis. Charles was trying to use the crusade to further his own ends, since the emir of Tunis had given support to his political enemies, the Hohenstaufens, and ceased to send tribute to Sicily.

Whatever Edward made of Louis’ change of direction, he had little choice but to follow. He duly sailed to Tunis and arrived there in early November, where he found the crusading army crippled with disease. Louis himself had been stricken down with illness and died on 25th August. Overall command of the expedition was handed over to Charles of Anjou, who had done so much to bring about this disaster. Unabashed, Charles entered into negotiations with the emir.

Edward was horrified at the state of the army and Charles’ willingness to deal with the enemy. He flatly refused to have any part in the treaty that was agreed, or accept his share of the war indemnity offered by the emir. Bristling for action, Edward declared he would lead his followers against the city of Tunis and destroy it. Charles prevented this, since the emir owed him seventeen years’ worth of tribute. He duly got his tribute, a fortune in gold and silver delivered on the backs of thirty-two camels. Edward cannot have been impressed with Charles’ attitude, which was hardly in keeping with the crusading spirit.

It was about this time that Edward made his famous declaration of intent: “By God’s blood, though all my fellow soldiers and countrymen desert me, I will go to Acre with my groom Fowin, and keep my word and my oath to the death!”

He was plainly determined to push on to the Holy Land, whatever anyone else chose to do. This did not mean Edward was deaf to common sense, and he agreed to the suggestion of Charles and other crusade leaders that the army should sail to Sicily. There they could spend the winter before going on to Acre, in the spring. Acre was the most important remaining Christian city and sea-port in the Holy Land, located on the coast between Haifa and Tyre. When the fleet sailed, Edward allegedly demonstrated his chivalric spirit by turning back to pick up two hundred crusaders left behind on the African coast – the only one of the leaders to do so.

After reaching Sicily, Edward finally experienced some good fortune when his ships were spared the consequences of a violent storm. His allies suffered terrible losses, with many vessels sunk or wrecked, horses drowned and treasure sent to the bottom. Wisely, Edward’s ships had taken up a more secure anchorage. The storm broke the spirit of many of the crusaders, who argued the expedition should be postponed for three years. Edward consented to the agreement, though he personally had no intention of abandoning the crusade. Unlike other leaders, who now gave up and went home, he stayed in Sicily. Only four conditions, he declared, would persuade him to abandon the cause: if a new pope was elected who forbad him to go to the Holy Land; if he fell ill; if his father died; or if civil war broke out in England.

Edward’s resolve was unshaken by even the most terrible piece of news. In March 1271, while still in Sicily, he was informed of the murder of his cousin Henry of Almain. Edward had previously sent Henry back to Gascony to see to affairs of state; he later claimed he had despatched him to bring about a reconciliation with the sons of Simon Montfort. On his way home Henry travelled via Italy and stopped to hear Mass at the church of St Silvester in Viterbo, north of Rome. Guy Montfort and Simon the Younger were also in Viterbo to meet their lord, Charles of Anjou, whose service they had entered after fleeing England. Once they learned of Henry’s presence, they went to the church and stabbed him during Mass. They left him dying, only to return and drag him out into the street, where they subjected Henry to the same mutilations their father had suffered at Evesham. ‘I have taken my vengeance,’ Guy was heard to remark before he and his brother fled.

For the moment, Edward could do nothing to avenge his cousin. In January he had hired more ships to carry him east, and at the beginning of May he sailed from Trapani for Cyprus, the last stopping-off point before Acre. Edward trusted in ‘the fortuitous breezes of the spring wind’ and was welcomed at Cyprus with great enthusiasm and ‘the highest honour’. The inhabitants had fond memories of his famous ancestor, Richard the Lionheart, who also visited the island on his way to the Holy Land.’

Edward didn’t tarry long in Cyprus. After a few days he set off on the final leg of the sea-crossing to Acre. Some merchant vessels of Cyprus accompanied his fleet, trusting in the English to protect them from pirates and Mamluk warships. A storm blew up shortly they left harbour, and Edward’s own ship almost foundered when it was hit by a great spout of water.

On 9th May 1271 Edward finally reached his destination, the port of Acre…

Is there any record or description of Edward’s wife giving birth on the Crusade? It seems that would have been a difficult aspect to the trip. Was she pregnant before the journey began? Though it seems to be a given that Joan of Acre was born during the Crusade, no one ever mentions it whilst describing Edward’s challenges.