Impregnable castles

In the high summer of 1266, royalist forces started to converge on Kenilworth. Protected by a formidable series of water and earthworks, and with a commanding view of the countryside, Kenilworth was one of the strongest fortresses in England. The rebel garrison, under the command of Henry Hastings, were confident they could hold out until Simon the Younger arrived from France with a relieving army. King Henry, for his part, swore he would not leave the siege until the castle was either taken or forced to surrender.

Edward moved his advance forces up to the castle on 21st June. Three or four days later, his father arrived with the rest of the royal army. The siege was an enormous undertaking, and Henry had collected men and equipment from all over the realm. His army was divided into four divisions, with the king himself in command of the assault on one side of the castle, Edward on another, his second son, Edmund, on the third, and Roger Mortimer on the fourth side. Mortimer had recently returned from the Welsh March and the loss of his army at Brecon. The terrible nature of that defeat doesn’t seem to have undermined the king’s faith in him as a captain, and he continued to play a loyal and active role in the fight against the disinherited.

The siege was extremely hard-fought, with heavy casualties on both sides. Edward organised the transportation of artillery from London, but the castle was also stocked with engines. Simon Montfort had been granted Kenilworth in the 1240s, and spent lavishly on turning it into an impregnable stronghold: Paris recorded the construction of ‘marvellous buildings’ and that the weaponry inside consisted of ‘unheard-of machines.’ He was writing in the 1250s, but the war engines may have still been in place at the time of the siege.

Now, after Simon’s death, his expenditure was to bear fruit. Both sides hurled volleys of stones at each other. They sometimes collided in mid-air. In an effort to take the castle by storm, Edward had special barges brought up from his estates at Chester at great cost. These were intended to ferry troops across the lake, but the attack was repelled. An enormous wooden tower was constructed, large enough to contain two hundred crossbowmen, along with another siege engine called the Bear (Ursus) with a compartment for archers. When these monstrous devices were rolled forward, they were smashed to pieces by missiles hurled from the castle wall. Every direct attack met with failure, and the royalists were eventually forced to try and starve the garrison into surrender. The aggressive confidence of the defenders was demonstrated when their captain, Henry de Hastings, cut off the hand of a royal envoy and sent him back to the king ‘with ridicule’.

Despite the close investment of the castle, the royalists were unable to prevent members of the garrison sallying out to pillage the countryside. The Waverley Annals noted that ‘the garrison of Kenilworth did not cease to plunder and destroy the surrounding country, taking fines from abbots and prelates in the area.’

Some examples of these raids are preserved. One Robert Oede, a knight of Harbury in Warwickshire, rode out with other ‘principal robbers’ and plundered a church at Wodeford in Northamptonshire, carrying stolen timber back to Kenilworth. Another member of the garrison, Robert Barde, was later accused of kidnapping a Henry of Nottingham and imprisoning him at the castle. Robert Fitz Alan, a Northamptonshire knight, also claimed he had been abducted and held prisoner at Kenilworth before managing to ‘escape secretly by night.’ Most of these incidents probably took place before the castle was surrounded by royal forces.

After the failure of the initial efforts to take Kenilworth by storm, there was little for Edward to do. His pregnant wife, Eleanor, was nearing the end of her term, so he took a break from military action and went to join her at Windsor. There, on the night of 13th July, she gave birth to their first son. Edward named the boy John, a controversial and perhaps deliberately provocative choice. At a time of war and baronial protest, choosing the name of his notorious grandfather King John – who had died in the midst of a civil war against his own barons – was remarkably bold. Or perhaps it was a deliberate statement on Edward’s part, implying the negative judgements of his ancestor by monastic chroniclers were not recognised by the royal family.

Occupation of Ely

In early August, while Edward was still at Windsor, dire news arrived of the re-emergence of John de Eyvill. After the sack of Lincoln, de Eyvill had retreated to the marshes of Axholme, from where he and his followers emerged to prey on travellers:

‘...he remains there in hiding, robbing

All who pass that way, burghers and merchants…’

One of de Eyvill’s victims was Peter Beraud, a member of a firm of Italian merchants that had taken loans from the Jewry and supplied Edward with money. De Eyvill and his men were later accused of having distrained, received and accepted the goods and merchandise of Peter, kept in ‘divers parts’ of Lincolnshire, and inflicted other severe losses on him. Striking at Italian merchants may have been an attempt to undermine Edward’s finances, crippling his ability to raise and maintain armies in the field.

On August 9th he descended on the Isle of Ely in Cambridgeshire, a region of low-lying fen and marshland similar to the Isle of Axholme. Ely was famous as the headquarters of Hereward, later known as ‘the Wake’, the famous hero of native English resistance against the Norman Conquest. It remained a useful centre of resistance, and was described in the mid twelfth century Gesta Stephani as ‘one impregnable castle…impenetrably surrounded on all sides by meres and fens…accessible only in one place.’ The author of the Gesta also advised on the best way to attack the isle:

‘Collect a quantity of boats at a place where the water surrounding the island seemed to be less wide, place them broadside on, and build a bridge over them to the shores of the island with a foundation of hurdles laid lengthwise.’

Dictum of Kenilworth

Edward remained in the background. He seems to have had little involvement in the drawing up of peace terms, known as the Dictum of Kenilworth. Issued on the 31st of October, the Dictum was a royal proclamation intended to reconcile the disinherited with the crown. King Henry, probably dismayed by the stubborn resistance of the disinherited, abandoned his earlier hard-line stance and offered a settlement. Via the terms of the Dictum, the disinherited were allowed to buy back their forfeited lands, at a cost depending on the scale of their involvement in the rebellion. The vital clause of the treaty is repeated below:

“Concerning the condition and business of the disinherited, among other things which we have ordained and established, wishing to proceed in the way of God and the path of equity, we have been led to provide, by assent of the venerable father Ottobono cardinal deacon of St. Adrian and apostolic legate of the Holy See and by assent of the noble Henry of Almain, having similar power, that there be no disherison but rather ransom, as follows. Those who fought at the start of the war and are still in arms; those who violently and maliciously held Northampton against the king; those who fought against and assailed the king at Lewes; those captured at Kenilworth after having sacked Winchester; those who have in other ways opposed the king and have not been pardoned; those who fought at Evesham; those who were in the battle at Chesterfield; those who freely and of their own will sent their followers against the king or his son; the bailiffs and officers of the earl of Leicester who robbed their neighbours and caused murder, arson, and other evils to be committed shall pay five times the annual value of their lands. If they pay this redemption they shall recover their lands.

Furthermore, if any one shall be forced to sell land, only he who holds it by gift of the lord king may buy it, if he offer as much as any other buyer and on the same terms. Similarly, if he who wishes to redeem his lands be forced to place the land to farm no one shall have greater right to farm the land than he who holds it of the gift of the lord king, and he shall have it on these terms that he be willing to give as much as any-one else to hold it at farm. He who gives satisfaction for all his land shall have full possession; if satisfaction be given for a half or a third part he shall immediately have a half or a third part. If the person redeeming his lands has not fulfilled his obligations at the last appointed term, half the remaining land shall remain with those to whom the land has been granted by the lord king. The person redeeming the land shall be free, within the said term, to see all or part of the land in the manner above mentioned, and similarly he may place the land to farm.”

The Dictum was only a limited success. Many of the lesser rebels were induced to come in and make their peace, but the garrisons at Kenilworth and Ely rejected the terms outright and vowed to fight on. They claimed the Dictum had been drawn up without their consent, the terms too harsh to be acceptable. They also objected to the Dictum’s declaration that the acts of Simon Montfort were invalid and unjust, and the effort to suppress his popular veneration as a saint. The rebels at Ely went further. John de Eyvill and his allies proudly declared their loyalty to King Henry and the Provisions of Oxford, affirmed their religious faith, invoked the memory of Earl Simon’s mentor (Robert de Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln) and pleaded the cause of those Montfortian bishops suspended by the king.

Fall of Kenilworth

Despite their continued defiance, nothing could hide the desperation of the garrison at Kenilworth. No relief army had appeared from France, and months of siege and bombardment had done their work. The castle was now so closely invested it was no longer possible for the rebels to send out raiding parties to gather supplies. Their food was running out, as well as firewood. Most of the roofs had been stoved in by royalist artillery. Cold and starving, on 8th November they begged a forty days’ truce in which to send envoys to Simon Montfort the Younger in France, to ask if he intended to send any military aid. This was granted. When the forty days expired, and it became clear no help would come from overseas, Henry de Hastings and his men finally agreed to surrender. The castle submitted on 20th December, and conditions inside were so revolting the besiegers were said to have been almost overcome by the stench.

The Battle of Ely

The reduction of Kenilworth left only the rebels at Ely to deal with. Or so it seemed. In January Edward moved between several coastal towns, probably gathering naval support for a waterborne assault on the isle.

A few weeks later, on 24th February, the king moved his headquarters from Bury to Cambridge. Here preparations were made for an all-out assault upon Ely. Henry fortified the town and surrounded it with a ditch, and in March gave orders for a fleet of ships to be collected from Norfolk and Suffolk. A number of skirmishes were fought between royalist troops and rebels. At Ramsey the aged King Henry himself, now 59, saw action:

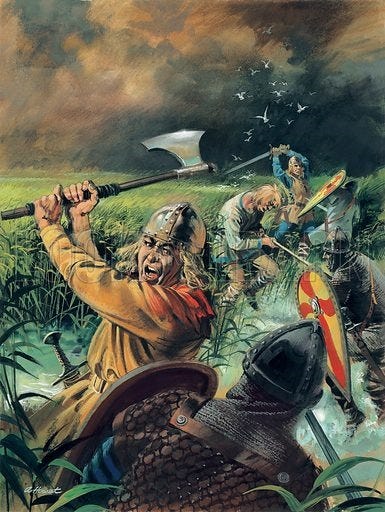

‘Therefore the king, setting out on his march towards Cambridge, stayed there for some time, being content for a time to check the attacks and hinder the escape of his enemies, who were in the aforesaid island. Therefore those bloodthirsty and crafty men found a passage out towards Ramsey, and according to their custom, they plundered all around, carrying off both men and cattle. When they heard this, the king and his followers came secretly to Ramsey, and finding there many of the malefactors, they slew some with the sword, some they took prisoners, others went and fled where they could.’

Henry also called upon the commons of the local counties to blockade the isle and to prevent the barons from ravaging the countryside. The effort at blockade ended in catastrophe when the rebels rode out in force and drove the ‘vulgar herd’ as far as Norwich. For good measure they pillaged the town, seized rich Jews and other men, and carried them back to the isle to hold for ransom. Knowing there was little to stop them, the barons widened their raids all over Cambridge and Huntingdon, plundering and slaying at will. Enraged, the king accepted an offer from the people of Lynn, who declared they would drive out the barons in exchange for a royal guarantee of their liberties. The Chronica describes their calamitous effort to storm the isle:

“Having gained what they asked, they assembled a large number of people of the lower orders, and proceeded with some vessels manned with crossbowmen, archers, and men armed in all kinds of ways, to capture the tenants of the island. The insurgents, being forewarned of their approach, planted their banners on the dry land, that those who were coming up the river might know where they were; and when the people of Lynn saw their troops and standards there, they exhorted their men to get on land with all speed. The insurgents then took away their banners, and feigned a flight, as if they did not dare to resist such a large force; and the citizens of Lynn, unaware of their stratagem, at once landed in all directions and in disorder, each and all of them intent on capturing the fugitives. The insurgents thereupon, returned, surrounded the citizens and their plebeian force, and slew them at pleasure, making prisoners of some who attempted to return to their vessels, and putting others to death. Great numbers perished in the river, and some few returned to Lynn, where they were received with derision.”

Doubtless to the king’s despair, fresh fires were breaking out all over the country. In March, while he prepared for the futile assault on Ely, rebels began to openly defy royal authority in Nottinghamshire. Roger de Leyburn, Edward’s lieutenant in the Cinque Ports campaign, was ordered to supply the garrison of Nottingham Castle with timber to build defences for the town. William Mortain, keeper of the peace for the county, was told to co-operate with Alan Kirkby, sub-constable of Nottingham Castle. Two engagements were fought with the rebels inside Sherwood Forest, in which the king’s men lost equipment and horses.

After his break from warlike activity, Edward was now sent back into the field. A new rebellion had sprung up in the north, this time in distant Northumberland.