In 1269, before going on crusade, Edward and his brother Edmund had taken steps to deal with Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby.

The earl was a problem. Since his capture in May 1266, shortly after the battle at Chesterfield, he had lain in prison at Windsor Castle. In a later age he might have been executed, but in 1266 there was still no precedent for the execution of an earl in England. Instead Ferrers was victim to a long and questionable process of disinheritance.

In June of that year, Edmund was granted all of the captive earl’s goods, and in early August all of his lands and castles. Via the terms of the Dictum of Kenilworth, it should have been impossible for Ferrers to be deprived of his estates in this way. King Henry and his sons, however, thought of a way of circumventing the Dictum. Unlike other rebels, who usually had to redeem their lands by paying five times their annual worth, the price of redemption for Ferrers was fixed at seven times. His punishment was greater, it was explained, because he had broken his earlier promises of good faith by going into rebellion again after 1265. The price of the earl’s redemption was fixed at £50,000.

Ferrers was supposedly ‘released’ from custody in 1st May 1269. In reality he was taken to the royal residence at Cippenham in Berkshire by Edmund, and forced to sign a series of deeds which guaranteed his disinheritance. He later claimed he only did so because he feared for his safety. It may well be that a threat of force, maybe even physical torture, was employed to make him comply. One of the four deeds Ferrers signed stated he had to pay the redemption fine of £50,000 before 9th July 1269, or else he would lose his inheritance. He also had to promise that his men would not interfere with this arrangement. This was to guard against the threat of the earl’s violent loyalists, those ‘men of Ferrers’ who had wreaked so much havoc during his first term of imprisonment.

Unsurprisingly, Ferrers was unable to raise the enormous redemption sum by the deadline. The 9th of July duly came and went, and all of his estates were duly passed back to Edmund. As Earl of Leicester (since the death of de Montfort) and Earl of Lancaster, this vast new acquisition of land and wealth made Edward’s brother one of the most powerful noblemen in the realm.

Once deprived of his power, Ferrers was allowed to go free. Edmund and Edward may have considered him harmless, not worth keeping in prison. They were wrong.

A neglected rebellion?

Soon after Edward departed on crusade, Ferrers struck. In November 1270, he and his followers forcibly reoccupied his old manor of Stamford in Berkshire. Stamford had been granted to Roger Leyburn, who was conveniently abroad with Edward in the Holy Land. Leyburn’s absence probably tempted Ferrers to try and snatch back his former estate. The regency government was quick to act, and the king’s brother, Edmund of Lancaster, despatched to drive out the intruders. This was done, and Ferrers obliged to withdraw in the face of royal troops.

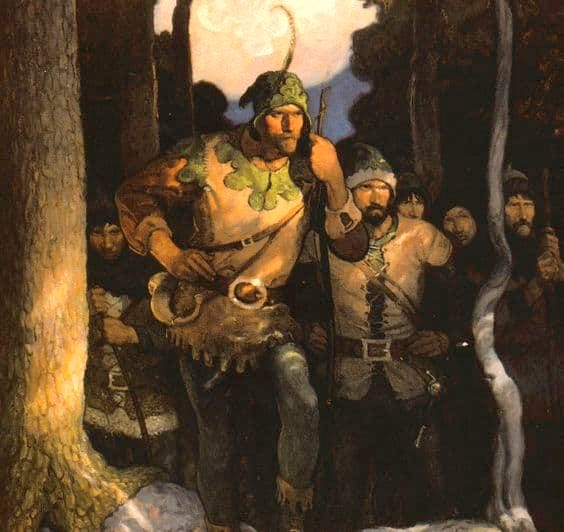

Roger Godberd

Ferrers’ activities between 1270 and 1273 are unknown, but it seems likely he was behind a large-scale rebellion that for a time completely engulfed the Midlands. The ostensible leader of this revolt was Roger Godberd, one of the men Ferrers placed inside Nottingham when he briefly held the castle in 1264 (see chapter 2). As explained previously, Godberd was a tenant of Earl Ferrers, and held the manor of Swannington in Leicestershire from him. In November 1266 Godberd had accepted the peace of the Dictum of Kenilworth, but didn’t remain in the peace for long. In 1267 he was probably among those rebels who fought two skirmishes against royal troops at Charnwood in Leicestershire and Duffield Forest in Derbyshire. The entry in the Patent Rolls states:

‘Whereas the king lately gave power to Edmund, his son, to admit to his peace all those of the counties of Derby, Stafford and Lancaster who were against the king, and had not yet come into his peace ; and the said Edmund accordingly admitted to the king’s peace all men who are of the tenure of Robert Ferrers, sometime earl of Derby, in the said counties, as it is testified by the said Edmund before the king; the king, accepting the said admission, has remitted them of all rancour and indignation of mind conceived towards them by occasion of the disturbance had in the realm, and all trespasses committed by them at that time, on condition that they behave faithfully henceforward, and that they stand to the award of Kenilworth; so that they inflict no damage or grievance upon any of the king’s faithful by reason of past enmity.’

Edmund of Lancaster was again heavily involved in the suppression of this revolt. In the same year, Nottingham itself was attacked by rebels from Duffield, who broke into the town and killed or wounded a number of citizens. Edmund, lodging in the castle, rode out to arrest the malefactors and imprison them in the castle dungeon. They were later released in return for a fine of 1,000 marks. Two years later, when the rest of England was at peace, the men of Ferrers were reported to be still at large and causing disturbances. The earl had been in prison since May 1266. His tenants fought on his behalf, just as they had during his first period of captivity in 1265. In 1271 another skirmish was fought between the Nottingham garrison and local outlaws, this time at Thorpe Peverel (the village of Perlethorpe):

‘Inquisition :—Sir Roger Lestrange, his esquires and men, sustained loss in a conflict at Thorpe Peverel with William Denyas and his supporters, robbers, to wit, Sir Robert de Stafford lost a horse of the price of 201.,Reynold de Paunceford a horse of the price of 24 marks, Calwe a horse of the price of 20 marks, Thomas Corbet a horse of the price of 10/., Stacy de Unfranvill a horse of the price of 10/., Adam de Birun a horse of the price of 10 marks, Richard Martel a horse of the price of 20 marks, Adam de Cateby a horse of the price of 10/., John de Stafford a horse of the price of 10 marks, Llewellyn de Sees a horse of the price of 10 marks, Nicholas Martel a horse of the price of 10/., Stephen de Fraunketon a horse of the price of 10 marks, Thomas Hody a horse of the price of 10 marks, Nicholas le Venur a horse of the price of 100s., Robert de Burton a horse of the price of 100s., Henry le Mareschal a horse of the price of 100s., Roger de Beautoft a horse of the price of 10 marks; there were also lost there 5 pairs of iron covertures of the price of 25/., 6 pairs of trappings (trappes) of the price of 6/., 3 breastplates of the price of 6 marks, 3 pairs of iron spurs of the price of 20s., and 3 ironhead pieces (palette) of the price of 6s. Unknown men of the country carried away the said harness.’

The royal troops clearly didn’t fare very well in this fight, and lost a number of horses as well as valuable gear. Roger Lestrange was lord of Cheswardine near the Welsh March; it seems the battle-hardened Marchers were being deployed to quell the disturbances in the midlands. One of his men, Stephen Fraunketon or Frankton, was later said to be heavily implicated in the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales.

Roger Godberd was not officially identified as leader of the rebels in the Midlands until a remarkable Patent Rolls entry from 1272:

‘Whereas on the showing of the magnates of the council and the Westminster, complaint of many others the king lately understood that in the counties of Nottingham, Leicester and Derby, as well in the common ways as in the woods, numbers of robbers, on horseback and on foot, were abroad and that no religious or other person could pass without being taken by them and spoiled of his goods, and perceiving that without greater force and stouter pursuit these could not be taken or driven from the counties, he, after consultation with the council, ordered that 100 marks should be levied of the said counties and paid to Reginald Reynold de Grey to attach them; and whereas the said Reynold has pursued them manfully and captured one Roger Godberd, their leader and master, and delivered him to prison, and W. archbishop of York, has delivered 100 marks of his own to the said Reynold as the king ordered, the king wills that that sum shall be levied of the said counties, to wit, 35 marks of Nottingham, 35 marks of Leicester and 30 marks of Derby, and paid to the archbishop for his loan so made, and commands all persons of the counties to contribute their proportions and to be intending to their sheriffs, who have been commanded to levy the same and deliver it to the archbishop, in levying this.’

This entry reveals the counties of Nottingham, Leicester and Derby had been completely overrun by an army of robbers led by Godberd, their ‘leader and master’. As a loyal tenant of Earl Ferrers, Godberd’s revolt was most likely triggered by the ill-treatment of his lord in 1269, when Ferrers was forced to sign away his inheritance. In other words, this was no random crime spree. Godberd was politically motivated and working hand-in-hand with the earl. The Patent Roll describes Godberd pursued ‘manfully’ and delivered to prison by Reynold de Grey – lord of Wilton in the Welsh Marches – in charge of a force raised by monies levied from the affected counties by the Archbishop of York.

Before Godberd’s revolt could be put down, his lord Ferrers swept into Staffordshire.

Envy and rage

The earl’s target was Chartley, another of his old manors. Chartley had been granted by Henry III to Hamo Lestrange, elder brother of Roger.. In 1271 Ferrers and a multitude of his followers attacked the manor at dead of night and killed a royal officer. Afterwards they seized Chartley Castle and occupied it, driving out the garrison. The rebels set about felling, selling and wasting the woodlands of the manor, perhaps to raise money to support their revolt.

Ferrers appears to have held onto the castle until 1273. By then his ally Roger Godberd was in prison, having been captured at the Northgrange, a grange inside Sherwood Forest belonging to Rufford Abbey. The suppression of the revolt in the Midlands allowed the royal forces to concentrate on Chartley. Edmund of Lancaster, Reynold Grey and Henry Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, were ordered by the regency council to attack the castle and deliver it ‘without delay’ from the king’s enemies. Meanwhile the Sheriff of Salop (Shropshire) and Staffordshire was instructed to raise the power of the county (posse comitatus) and drive out the rebels from the surrounding manor and woods.

England was in danger of slipping back into civil war. Shortly before the combined royal army laid siege to Chartley, a rumour reached the council of fresh conspiracy in the north of England:

‘In the meantime, some persons in England, kindling with envy and rage, thirsting for money which did not belong to them, and prophesying of their own hearts, affirmed that Edward would never return to England. These men, wishing to make sure of future events, collected in the northern provinces some three hundred armed men, without counting infantry and light-armed cavalry; but they were pursued by some noble and powerful knights, namely, Edmund, brother of King Edward, and Roger Mortimer, with a large company of armed men. And when the confederate rebels heard this, their league was dissolved, and they returned to their own homes, without attempting any further achievement.’

Once again Edmund was at the forefront of events. He and Mortimer, now acting as co-regent – raced north and successfully crushed the rebellion before it had a chance to spread. Unfortunately the Flores gives no further details, so the identity and location of the rebels is a mystery. Given events elsewhere, this short-lived northern conspiracy was probably linked to the rising of Earl Ferrers and his followers.

Once the risings in the north and midlands were quelled, the royalist commanders turned all their attention to Chartley. The personal animosity between Edmund and Ferrers may have come into play, for the siege was a brutal affair: in 1282 Edmund, Lincoln, and Grey, among others of their party, were pardoned for deaths caused during the assault on Chartley Castle.

The castle was quickly taken, though Ferrers himself escaped. A number of his surviving followers were later pardoned for holding Chartley against the king’s forces. Most of these men appear to have been tenants of the earl’s former lordships in Derbyshire. Diehard retainers, prepared to follow their lord to the death. If nothing else, Ferrers must have had a gift for inspiring loyalty.

The return of the king

Gilbert Clare was nervous about the state of the kingdom. He wrote to the Chancellor, Robert Burnell, expressing his concerns:

‘It does not seem there can be any tranquillity in the land, nor is the king’s lordship worth anything if the people of the land can assemble forces like this in times of peace.’

Clare, despite his previous animosity against Edward, yearned for the king’s return. Only the presence of the monarch, and the authority he brought, could truly restore stability to England. Even after the suppression of Ferrers, the council still laboured under fears of rebellion and conspiracy. Orders were issued that nobody should be allowed to enter London armed, and Gilbert’s younger brother, Thomas Clare (who had recently returned from the Holy Land with four Saracen captives) appointed to advise the city authorities on defences. In May 1274 the council issued an order for all the boats in the Isle of Ely to be sunk, and a watch kept against ‘malefactors and suspected persons’ who had tried to re-enter the isle and occupy it, just like the disinherited in 1266-67.

All these fears were allayed by the return of Edward, who at last set foot on English soil again at Dover on 2nd August 1274. On the 18th he made a triumphant entry into London, where the streets were decorated in his honour. There was no sign of the former unrest, and his coronation on the 19th went ahead with great pomp. The conduit in Cheapside ran with red and white wine for all to drink, a feast was held, and five hundred horses released for anyone to catch. At the coronation ceremony Edward is said to have removed the crown as soon as it was placed on his head, saying ‘he would never take it up again until he had recovered the lands given away by his father to the earls, barons and knights of England, and to aliens.’

Edward began his reign in a spirit of conciliation. Being absent from the country for so long gave him a chance to start anew, and he had no intention of allowing the tensions in England to fester. Robert Ferrers was not punished for his recent rebellion, showing Edward’s willingness to set aside old grievances and private feuds. Ferrers spent the remainder of his days (he died in 1279) petitioning for the return of his estates. He could never hope to recover the whole of his patrimony, but in 1275 managed to regain the manor of Chartley, though not the castle. It may be that the king retained the castle, along with a garrison, in order to remind Ferrers of royal authority. Ferrers also succeeded in recovering his manor of Holbrook in Derbyshire, again by legal rather than violent means. His son and heir, John, would spend his life lobbying in vain for the restoration of the Ferrers patrimony.

The new king also extended mercy towards Ferrers’ ally, Roger Godberd. After his capture in 1271-2, Godberd was shunted about various prisons including Bruges (Bridgnorth in Shropshire) and Chester. In 1276 he was finally brought to trial at Hereford and Newgate. The transcript of his trial survives:

‘Hereford. The same Roger, accused as a public criminal of many burglaries, homicides, arsons, and robberies committed by him in the counties of Leics, Notts, and Wilts, and especially accused that he, together with other evildoers, wickedly robbed the Abbey of Stanley in the said county of Wiltshire of a great sum of money, horses, and other things found there, and also of the death of a certain monk killed there about the feast of St Michael in the 54th year of the reign of the lord king Henry, father of the present lord king [29 Sept 1270], comes and denies all burglaries, homicides, arsons, robberies and all larceny etc., except at the time of the disturbance recently happening in the kingdom between the lord king Henry and Simon, former earl of Leicester, and his accomplices. And whereof he says that the same lord king Henry received him into his peace and pardoned him for whatever he had done against his peace etc. up till the ninth day of December in the 51st year of his reign [1266], on condition that from then on he would conduct himself faithfully towards the king and his heirs, etc., and he puts forward letters of patent of the same king Henry which bear witness to the same. And he says that he has always thereafter conducted himself well and faithfully towards the said king and his heirs and everybody else, and that he is not guilty of any of the foregoing, and for good and ill he puts himself on the country of the aforesaid counties. And so the sheriffs of the aforesaid counties were instructed to cause, each from his own county, 12 men to come before J. de Cobbeham, (justice appointed to deliver Newgate Gaol) at London [marginated: London] three weeks after Easter to decide the matter. (There now follow, in the shortened form, the standard formulae – 12 jurors by whom the matter will be considered, who are not related to the parties, because the defendant has asked for a jury trial.) And the sheriff of Hereford was instructed to cause the said Roger to come there on the said date.’

Godberd’s spirited defence relied on letters patent he had received from the old king, Henry III, when he came into the peace at Kenilworth in 1266. These letters gave him no protection against crimes committed after that date, so by rights Godberd ought to have been convicted. Instead he was evidently acquitted and released. In 1278 he and several other men were accused of robbing one Richard Coleshill at Stanton in Leicestershire. Godberd was still alive in 1287, when he and his old comrades from Nottingham Castle were accused of poaching in Sherwood Forest, way back in 1264; a classic example of the inertia of medieval justice. He was dead by the early 1290s when his son, another Roger, took over the tenancy at Swannington.

Roger Godberd probably owed his unlikely salvation in 1276 to the king’s influence. No such mercy was shown to Walter Devyas, one of Godberd’s criminal associates, who in 1272 was convicted and beheaded while Edward was still abroad. By showing mercy to Ferrers and Godberd, just as he had to the leaders of the disinherited, Edward sought to heal old wounds and unite the community of the realm under his kingship.

APPENDIX A: Edward and the tournament

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Medieval Realms to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.