After his return from Lincoln, Edward went in pursuit of another band of rebels in the south. Their leader was Sir Adam Gurdon, lord of Selbourne in Hampshire. A staunch Montfortian, prior to Evesham Montfort had made him warden of Dunster Castle near Minehead in Somerset. In July 1265 Adam had a chance to prove his worth when a band of Welsh pirates, led by one William Berkeley, landed in Somerset to ravage the countryside. Rishanger describes what followed:

‘In that year, on the Sunday before the battle of Evesham, a multitude of Welshmen having as their captain, William de Berkeley, a knight of noble birth but of infamous character, landed at Minehead, near the castle of Dunster, in order to ravage the county of Somerset. The warden of the castle, Adam Gurdon by name, came out to meet them, slew many of them with the sword and putting many others to flight, among whom was the captain, caused them to be drowned.’

Adam seems to have stayed at Dunster instead of joining Montfort at Evesham: a later inquisition says that one of Adam’s followers, Robert Bingeham, ‘retired thence’ to Dunster long before the battle. By the spring of 1266, according to Wykes, Adam had made himself the leader of a band ‘like-minded evil minions’ that plagued the south of England. His main stamping ground was the forest of Alton in Hampshire, not far from his manor at Selbourne, though he did range further afield: the Annals of Dunstable mention him raiding the manor of Shortgrave in Bedfordshire.

The raid on Shortgrave was destined to be Adam’s last. He and his company of 80 horsemen (including David of Uffington, another rebel knight) spent all day at Shortgrave, eating, and then rode off taking all they could carry. The outlaws journeyed back to Alton via Kimble and the Chiltern Hills. They were being followed. One of Adam’s followers, Robert Chadde, had turned traitor and offered to lead the Lord Edward to the outlaw camp.

Edward and his followers attacked the outlaws as they were busy laying an ambush in the wood for passers-by. He immediately challenged Adam to ‘defend himself like a brave man’, and the two engaged in single combat. A fuller account is given by Wykes:

‘And lord Edward, in order that he did not seem to be doing nothing, in the same week of Pentecost was cunningly wandering through the divers small hidden parts of the places, and, having been protected by the careful providence of spies, found lord Adam Gurdun, who had invaded the southern parts of England, in a certain wood near Aweltone around sunset, encamped with his abominable troop, and boldly unsheathing his sword, he rushed upon him. And the gigantic and very invincible warrior attacked him alone like a soldier; for the troop, who, being about to offer help to him, ought to be following him, being hindered by a certain small ditch, could not come to him so swiftly; on which account a braver man was forced to fight with a brave man very bravely; for the said Adam was a strenuous knight and very strong warrior: but at length lord Edward prevailed over the cruel ruler with his men bringing help to him, and he took him captive, with very many men of his troop having been cruelly killed, and after a savage wound had been inflicted. And he took him with him as far as Windsor, and, just it was suitable, he burdened him with terrible shackles, in order that by chance the earl of Ferrers, having been made a captive there, might not remain without a companion.’

The Chronica gives a slightly different version of the duel:

‘Edward being desirous of trying the strength and courage of this man, whose fame had reached his ears, marched against him with a strong body of troops; and as he was preparing for battle, Edward gave orders to his followers not to interfere to prevent a single combat between them. The two therefore met, and continued to exchange repeated blows at one another with equal effect. For a long while they fought without either party giving way to the other, when Edward, delighted at the valour of the knight and his courage in battle, advised him to surrender himself, and promised him his life and a good fortune.’

Wykes, for all his admiration of Edward’s courage and prowess, implies the latter charged into combat without realising he was cut off from his followers by a ditch. Fortunately Edward was able to defend himself until his men could come to the rescue. The Flores claims Edward ordered his men not to intervene before he engaged Adam in combat and defeated them. Both accounts have a ring of truth, and are reminiscent of Edward’s headstrong charge at Lewes. Edward had learned a great many lessons since that day, and matured into a patient and effective commander, but the impetuous streak was still there. Engaging a dangerous outlaw knight in single combat was brave, the stuff of Arthurian legend, but hardly wise. Adam was a seasoned warrior, and the duel might have easily resulted in Edward’s injury or death.

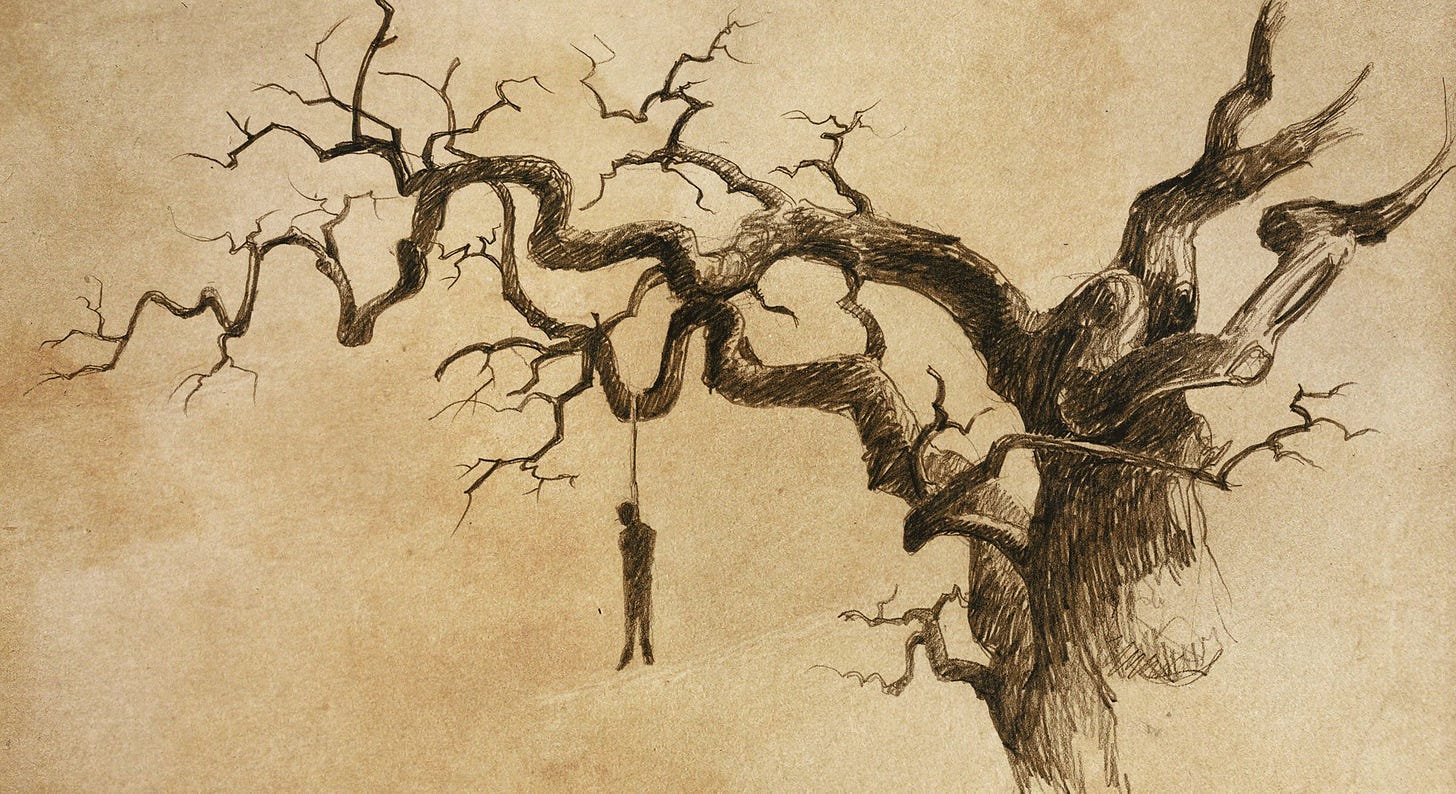

The attack on Aweltone ended in complete success. Adam was defeated and sent off in chains to join Earl Ferrers in captivity at Windsor. No such mercy was extended to his followers, who were either butchered on the spot or hanged on the trees around their camp. A few escaped. The names of some of these unfortunate men are preserved in a series of inquisitions, held just after Evesham, into the lands held by rebels.

Adam Gurdon’s later career is an interesting example of how former rebels were converted into useful royal servants. A legend grew up around the tale of his knightly duel, claiming Edward was so impressed with Adam’s valour he offered him life and fortune if he would surrender. The reality was harsher. After Adam’s capture Edward gave him to the Queen as a prisoner, and he had to buy back his lands at a heavy price. When Edward became king, Adam’s talents were not wasted. In 1277 he served against the Welsh under the command of Roger Mortimer at Montgomery. He was appointed Keeper of Alice Holt Forest and Woolmer Forest, and serves on various commissions as a justice and warden of the Hampshire coast. A long-lived man for his era, he eventually died in 1305. The former outlaw and robber knight had been thoroughly rehabilitated, yet another example of Edward’s capacity to turn former enemies into useful servants.

In the spring of 1266, after much hard fighting, the royalists were again in a strong position. The rebel headquarters at Axholme and the Cinque Ports had been reduced, the disinherited crushed at Chesterfield, the outlaws in Hampshire defeated. The Montforts were in exile or prison, Robert Ferrers and Adam Gurdon both in royal custody at Windsor. Only John Eyvill and his supporters remained at large, but they would have to be dealt with later. For now King Henry and the Lord Edward turned their attention to Kenilworth, the last major rebel base of any note.

tis but a scratch

Given how much time Edward spent on the tourney circuit, this must have been an opportunity to mix work and sport.